Cancer Screening

All screening programmes do harm; some do good as well.

Sir Muir Gray, Former Director of the UK National Screening Committee.

Table of Contents

What is Cancer Screening?

Dangers of Screening: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

Prostate screening: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

Lung screening: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

Bowel Screening

Cervical Screening

What is Cancer Screening?

Checking for disease when there are no symptoms. Examples of cancer screening tests are the mammogram (for breast cancer), colonoscopy (for colon cancer), PSA test for prostate cancer, and the Pap test and HPV tests (for cervical cancer).

See separate article on Breast Cancer Screening

Dangers of Screening: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

Definition of Overdiagnosis

Source: National Cancer Institute

Finding cases of cancer with a screening test (such as a mammogram or PSA test) that will never cause any symptoms. These cancers may just stop growing or go away on their own. Some of the harms caused by overdiagnosis are anxiety and having treatments that are not needed.

Some cancers that are diagnosed early do not develop symptoms requiring treatment, while others grow so slowly that the patient outlives the cancer and dies of other causes. Many of these are treated unnecessarily, leading to:

- Unnecessary tests and treatment

- Exposure to dangerous side-effects

- Radiation-induced cancers

- Mental and physical pain

- Infertility

- Inflated survival rates

This 2019 Opinion Article published in Nature Reviews Cancer says: For cancer screening to be successful, it should primarily detect cancers with lethal potential or their precursors early, leading to therapy that reduces mortality and morbidity.

Screening programmes have been successful for colon and cervical cancers, where subsequent surgical removal of precursor lesions has resulted in a reduction in cancer incidence and mortality.

However, many types of cancer exhibit a range of heterogeneous behaviours and variable likelihoods of progression and death. Consequently, screening for some cancers may have minimal impact on mortality and may do more harm than good.

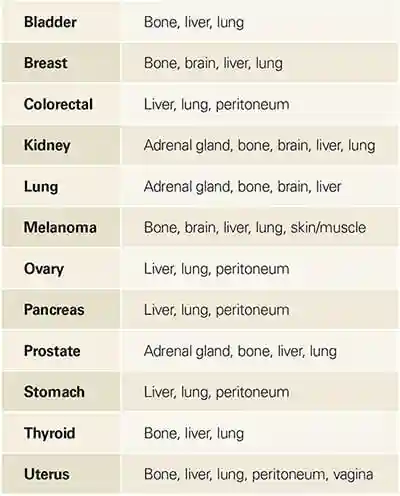

Prostate, Breast, Renal, Thyroid cancers, and Melanoma

This 2020 study found: After analysing changes in absolute lifetime risks for prostate, breast, renal, thyroid cancers and melanoma between 1982 and 2012, we estimated that 18% of all cancers diagnosed in women (ie, 11 000 diagnoses each year), and 24% of those in men (18 000 each year) are overdiagnosed cancers.

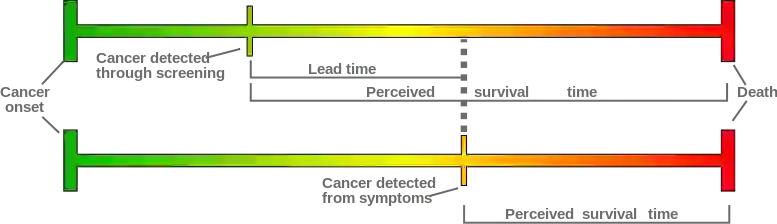

Lead time bias

A distortion overestimating the apparent time surviving with a disease caused by bringing forward the time of its diagnosis

The way statistics are manipulated is through the whole idea of early detection. Since cancer treatment success is measured on surviving five years after the first date of diagnosis, all we need to do in order to give the perception of greater success is to diagnose the patient earlier…

In his book The Cancer Code: A Revolutionary New Understanding of a Medical Mystery Dr Jason Fung explains:

Much of the benefit of screening is illusory due a phenomenon known as lead time bias. Imagine two women who both develop breast cancer at age sixty and who both die of the disease at age seventy. The first undergoes screening and finds the disease at age sixty-one. The other does not undergo screening and finds the disease at age sixty-five. The first woman “survived” cancer for nine years, whereas the second “survived” cancer for only five years. Screening improved cancer survival by an apparent four years, but this is only an illusion.

Figure: Lead time bias By Mcstrother – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15703636

A major study on cancer survival examined data over a 45 year period and found that “changes in 5-year survival rate over time bear little relationship to changes in cancer mortality.”

Prostate screening: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

In this study, Etzioni et al found that one in three prostate cancers diagnosed by screening for prostate specific antigen (PSA) is an over-diagnosis.

This study says:

With repeated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing and 10–12-core biopsy of the prostate, often done repeatedly, small, low-grade tumours are frequently detected. Attesting to the relatively low biological potential of these lesions are the 99% and 97% disease-specific survivals at 5 years and 10 years of follow-up, respectively, for men who are simply monitored and only given treatment if they have evidence of a grade or volume increase. Despite this indolent behaviour, greater than 90% of these tumours are treated with radiation or surgery, generating morbidities of treatment (eg, sexual, urinary, and gastrointestinal side-effects, in about 15–20% of patients), increased risk of secondary malignancies (with radiation), and increased cost.

Lung screening: Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

This study says:

…70% of patients with stage I disease survive for 5 years, and 40% of those with stage II cancers. This finding has prompted major efforts to develop early detection programmes. However, lung cancer screening studies and autopsy reports suggest that a substantial subset of screening-detected cancers are indolent, even in the setting of a cancer type often thought to be aggressive, with 20–25% of cancer detected estimated to be overdiagnosed.

Bowel Screening

In Ireland – a BowelScreen Test Kit is offered free to men and women aged 60-69 by The National Bowel Screening Programme

This is a test you carry out in your own home.

You can also purchase the kit from PrivaPath Diagnostics

Other countries:

Test kits may be supplied by your Health Service or can be purchased in pharmacies and online.

Cervical Screening

What cervical screening is

Source: Health Services Executive

A cervical screening test checks the health of your cervix. The cervix is the opening to your womb from your vagina.

It’s not a test for cancer, it’s a test to help prevent cancer from developing.

Screening first looks to see if you have any of the high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV) that cause cervical cancer.

If HPV is found, your same test sample will be checked to see if you have any abnormal (pre-cancerous) cells in your cervix.

This is a new way of screening. It is called HPV cervical screening. It was introduced in Ireland in March 2020.

HPV cervical screening:

- is a better way of cervical screening

- prevents more cancers

- means some people will have fewer tests

If you have had a smear test in the past, having a cervical screening test will feel the same.

Key things to know about cervical screening

- It’s not a test for cancer, it’s a test to help prevent cancer from developing.

- All women or people with a cervix aged 25 to 65 should be invited for regular free screening by letter.

- During the screening test, a small sample of cells is taken from your cervix.

- The sample is tested for human papillomavirus (HPV).

- HPV can cause abnormal cell changes in the cervix.

- HPV is the main cause of cervical cancer.

- If your sample tests positive for HPV, we will check for abnormal cells.

- Abnormal cell changes are sometimes called pre-cancerous cells.

- In most cases, it takes 10 to 15 years for cells in the cervix to go from normal to pre-cancer to cancer.

- Finding HPV or abnormal cells early means you can be monitored or treated so they do not turn into cervical cancer.

- You’ll get your results by letter, usually about 4 to 6 weeks after your screening test.

What causes cervical cancer?

Source: The website of the National Cancer Institute

Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by infection with oncogenic, or high-risk, types of human papillomavirus, or HPV. There are about 12 high-risk HPV types. Infections with these sexually transmitted viruses also cause most anal cancers; many vaginal, vulvar, and penile cancers; and some oropharyngeal cancers.

Although HPV infection is very common, most infections will be suppressed by the immune system within 1 to 2 years without causing cancer. These transient infections may cause temporary changes in cervical cells. If a cervical infection with a high-risk HPV type persists, the cellular changes can eventually develop into more severe precancerous lesions. If precancerous lesions are not treated, they can progress to cancer. It can take 10 to 20 years or more for a persistent infection with a high-risk HPV type to develop into cancer.

In an interview with National Public Radio, Donald Lannin, a professor of surgery at the Yale School of Medicine, who led the study, said “It takes 15 or 20 years for [these small tumors] to cause any problems. And you can kind of imagine that a lot of patients will die of something else over that 15 or 20 years.

See also

Breast Cancer Screening

The National Cancer Screening Service (Ireland)

Page updated 2024